For a quarter of a century we have sought to memorialise the victims of communism by erecting monuments and opening museums. But at times it seems that the most important things continue to be left unsaid.

Despite the Institute of National Remembrance operating at full capacity, it cannot win against nature. Defendants usually avoid justice, through death or for reasons of old age. Had the Institute of National Remembrance been formed ten years before, and had judges party to the lawlessness of the Polish People’s Republic been duly charged, justice would probably have had a better chance.

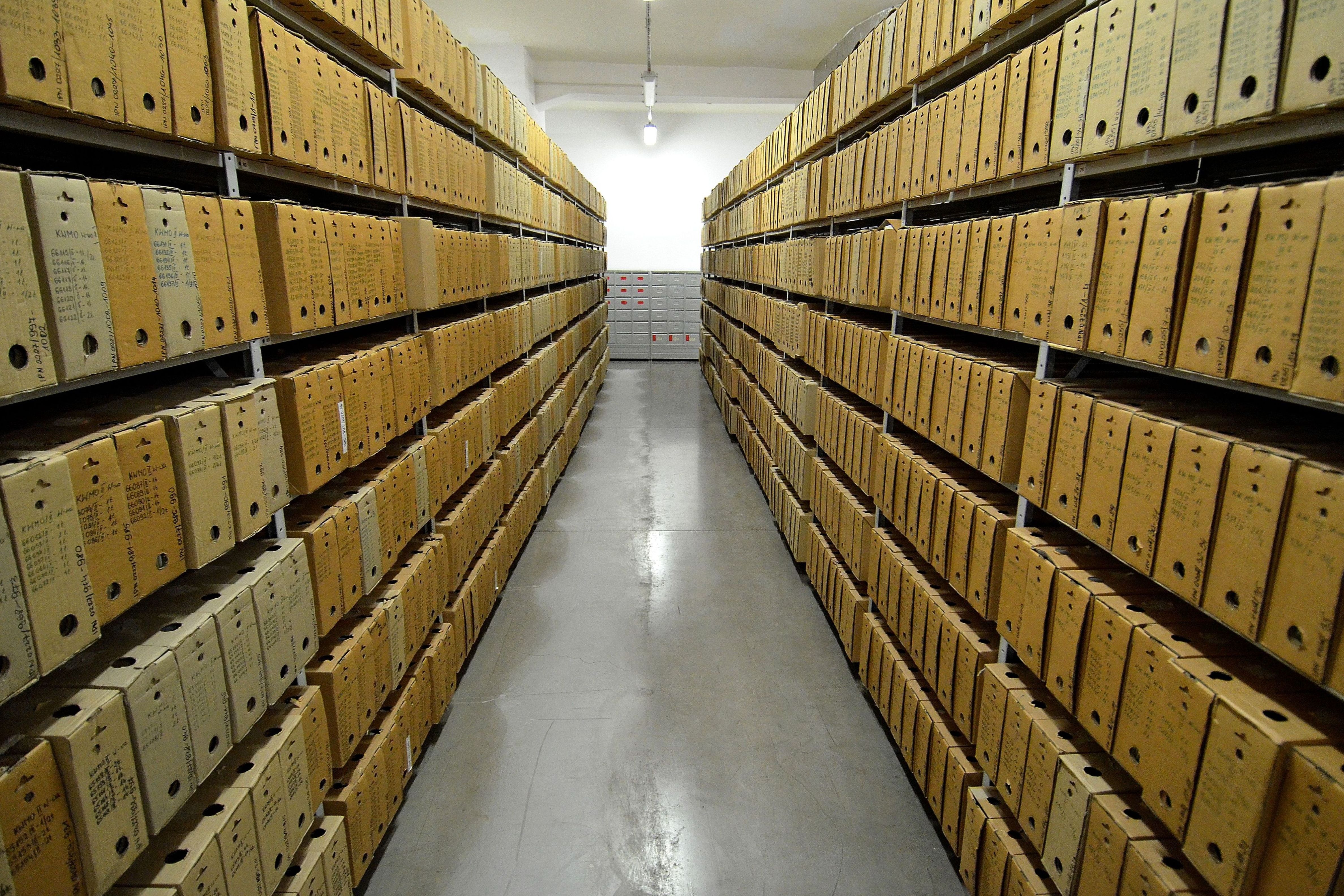

Institute of National Remembrance Prosecutions

As of October 2013, Institute of National Remembrance judges closed proceedings in 12,457 cases. Over a period of ten years, a total of 305 cases were filed against 469 individuals. 131 were convicted, with as many as 129 for communist crimes. Proceedings against 13,562 defendants were discontinued because of the statute of limitations. Nonetheless, prosecution is not over. Last year, as many as 1,252 new proceedings were initiated, 704 of which were in cases relating to communist crimes. During the same period, Institute of National Remembrance prosecutors filed as few (or perhaps as many) as 10 cases against 12 defendants.

Prosecuting crimes, communist crimes in particular, is but one of the aspects of coming to terms with the Polish People’s Republic’s past (and of the Institute’s work). A list of examples of the work performed during recent weeks follows, as reported by the Polish Press Agency.

- (18/11) Following a preliminary examination, the Institute of National Remembrance defined the area to be searched in the hope of identifying the graves of Home Army soldiers Danuta ‘Inka’ Siedziko wna and Feliks ‘Zagon czyk’ Selmanowicz at the Gdan sk Garrison Cemetery, in the vicinity of a prison where both had been sentenced to death after prolonged and cruel interrogation.

- (15/11) In the case of Stalinist military prosecutor General Marian R., aged 94, charged with having unlawfully deprived 17 detainees of freedom in the years 1951–1954, the Regional Military Court in Warsaw withdrew the majority of charges by virtue of the 1989 amnesty, and a number of other charges due to the statute of limitations. The Institute of National Remembrance is set to file an appeal. Following the so-called Gomułka period of political thaw, R. was chief military prosecutor of the Polish People’s Republic, then chairman of the Polish Football Association, and director general of the Office of the Council of Ministers in the 1980s.

- (21/10) The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg concluded that it cannot assess the 1990–2004 Russian investigation into the Katyn massacre, as Russia ratified the European Convention of Human Rights only in 1998, i.e. eight years after the investigation had begun. The judgment received heavy criticism, including from Professor Witold Kulesza, former head of prosecution at the Institute of National Remembrance, who said that ‘the court had an opportunity to add something of a postscript to the judgment of the Nuremberg Trials by confirming that the Katyn massacre had been committed by Russia, which today is charged with the duty of classifying the crime in international law as genocide. Let me add that the Institute of National Remembrance is conducting its own investigation into the Katyn massacre, the outcome of which largely depends on the files held by Russia. To date, the authorities there have failed to provide Poland with a complete set of documents.’

Live Fire Fight

I cite the Strasbourg judgment in the Katyn case to prove that seeing justice done is an uphill struggle, even outside of Poland.

This is shown in the ruling of the Regional Court in Warsaw in the December 1970 case. Over eighteen years of trial, the number of defendants has shrunk from twelve to three. That in itself is cause for a major charge to be brought against today’s Polish judiciary. The court acquitted former deputy prime minister of the Polish People’s Republic Stanisław Kociołek, while sentencing two commanding officers of troops responsible for crushing the December 1970 worker protests to two years of suspended imprisonment sentences. Concurrently, the legal classification of charges was commuted from issuing a command resulting in the manslaughter of several individuals at the Gdan sk and Gdynia Shipyards to participation in an assault resulting in death with the use of ‘dangerous objects’, the dangerous objects in question being rifles loaded with live ammunition. In her justification for commuting the charges the judge, Agnieszka Wysokin ska-Walczak, declared as follows: ‘Responsibility for participation in battery resulting in death does not require blame to be individualised; the relevant article of the Polish Criminal Code extends to fights and well as assault threatening human life and health.’

The legal structure resulting in Polish People’s Army officers having been convicted for participation in battery resulting in death (Article 158 § 1–2 of the Polish Criminal Code), while probably easier for evidence-related reasons, dilutes the perpetrators’ accountability.

Maciej Bednarkiewicz, the lawyer representing the victims in the December 1970 trial, who announced his intention to file an appeal, told the Rzeczpospolita daily that he expects the Appeals Court to offer an appropriate assessment of the Polish People’s Republic under criminal law, as this is the last moment to do so. The President of the Institute of National Remembrance shares this opinion. In March 2012, he called on the individuals with access to knowledge of events qualifying as communist or Nazi crimes to come forward and testify before a commission (the Ostatni Świadek – Last Witness campaign). The campaign yielded the initiation of investigation proceedings in 38 cases.

The Lost Decade

You might well ask why so late? And why has Poland been so slow to prosecute communist crimes? Maciej Bednarkiewicz, a lawyer with ample experience in political trials, believes that three factors have contributed to deficiencies in justice against officials of the Polish People’s Republic: that in the wake of 1989, they only handed selected files over to the new authorities; that the current Polish Republic and its authorities have not been sufficiently persistent in bringing criminals to trial, and have suffered a shortage in support; and that the 1981 imposition of martial law or the Polish People’s Republic have never been judged in political categories, as was the case in Germany.

‘The primary obstacles encountered by Institute of National Remembrance prosecutors are legal in nature: doubts as to the statute of limitations for communist crimes,’ adds Dariusz Gabrel, director of the Chief Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation.

The fundamental issue is that, in the resolution of May 25, 2010 (Reference No. I KZP 5/10), the Supreme Court interpreted provisions of the Institute of National Remembrance Act with regard to the statute of limitations for communist crimes, concluding that the Institute of National Remembrance does not have the capacity to prosecute crimes carrying a penalty of up to three years of imprisonment.

‘There are factual problems as well,’ highlights Gabrel, ‘such as the passage of time: the memory of witnesses dims, after many years it becomes impossible to identify the victims, and there are difficulties with collecting evidence. In the 1990s, it would have been easier to prosecute the perpetrators of communist crimes, but parliament only began dealing with the issue in late 1998 by establishing the Institute of National Remembrance.’

‘Officials from the Office of Public Security and Security Service have used the occasional argument that they felt unjustly treated; the Institute of National Remembrance is prosecuting them, they are facing charges of torturing an innocent human being, and yet, they say, this human being had been tried and sentenced by a court of law. Why, then, should they be treated any differently to judges in facing criminal responsibility for alleged lawlessness,’ says Professor Witold Kulesza.

This brings me to the role of the prosecutors and judges of the Polish People’s Republic.

Judges with Immunity

Poland has not seen the sentencing of any prosecutor or judge for judicial crimes comprising the trying and sentencing of innocent individuals recognised as opponents of communist authorities, despite the fact that more than 100 officials who tortured these innocent individuals in person have actually been tried and convicted.

It is thus difficult to claim pure coincidence. What usually happens resembles the Katowice case: the local branch of the Institute of National Remembrance was investigating communist crimes consisting of the abuse of power by prosecutors and judges who under martial law in 1981/82 had tried Solidarity Trade Union members, sentencing them to imprisonment. These Solidarity members were convicted for acts which were not illegal under the law, making it obvious that the issue was one of political repression. The Institute of National Remembrance applied to the respective courts (including the Supreme Court, as one of the judges had been a Supreme Court judge, currently retired) to remove the respective prosecutors’ and judges’ immunity, allowing them to be tried under criminal law. Not only did the Supreme Court refuse the institute’s motion, on December 20, 2007 it resolved that criminal courts had been forced to apply the Martial Law Order in retrospect. As the 2007 resolution was entered into the Register of Legal Statute, lower-instance courts are currently treating it as binding interpretation.

‘When as a co-author of the Institute of National Remembrance Act I was consulting it with German prosecutors appointed to prosecute cases of lawlessness in the German Democratic Republic, they envied the institute’s investigation authority,’ recalls Professor Witold Kulesza. ‘But they also pointed out that commencing any investigation in the late 1990s, ten years after the collapse of communism, is too late for the democratic state to judge the crimes in question. They told me that we were just beginning a process they were about to complete. I must admit the bitter truth that my German colleagues were correct.’

This article was originally published in a special appendix to Rzeczpospolita daily for the 'Genealogies of Memory' conference on 27 November 2013.